View up the now mainly ice free fjord this week. Photo: Hannah Wood

A catchy title! It seems to have been a while since I have written a blog. I think because we have settled into life here all the amazing things we do each day seem somehow less newsworthy. However I thought I would give you a general update on the goings on over the past week, both inside the laboratory, and generally about town. So perhaps I should start with the science as this is the bit that occupies most of our waking hours.

Helen and I have been working on the urchin fertilisation experiment this week which has been interesting, hardwork and a lot of fun too. It started off with selecting some urchins to spawn. We chose mainly larger urchins for this in the hopes they would contain more eggs or sperm. One of the main problems we faced is that unlike a lot of animals, particularly mammals, there is no easy way to tell whether a sea urchin is male or female. Because of the way in which they reproduce there is also no particular need for the urchins to be able to tell whether the urchin next to them is male or female. When they reproduce they do so by what is known as broadcast spawning. Based on some cue from the environment (with urchins this is usually a mixture of light levels and temperature increase) the urchins all release their eggs or sperm in a big synchronised event. The sperm then fertilises the eggs in the water column, the eggs develop into larvae which looks very different from an adult sea urchin. Then when they are developed enough the larvae settle on the sea floor and turn into the form a of a sea urchin that you would recognise. Broadcast spawning may not seem the most effective method of reproducing at first glance, particularly as a high degree of synchronicity is required to ensure that the eggs are fertilised. However it is effective and the most common method of reproduction in marine invertebrates; for example the corals on the great barrier reef in Australia all spawn each year in one event so big that if you dive at that time you can hardly see through the water. Anyway enough of that, back to the cold cold waters of the arctic and the urchins. As I said we did not know which urchins were male and which were female. For our experiment we needed to collect the eggs of five females and mix it with the sperm from one male; that way all the developing larvae would be half siblings. Based on our earlier trials I though we’d have plenty of females. So we set up 8 urchins over pots in which we were to collect the eggs, then injected potassium chloride into them; this chemical should be kept well away from humans (it doesn’t have the same effect so no home experiments please) but in invertebrates it makes them spawn their eggs/sperm. We ended up with more males and females on our first attempt. So we started some more and had just the right amount to begin.

Spawning urchins; a male on the left and a female releasing eggs on the right. Photo: Bonnie Laverock

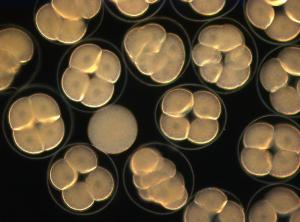

We mixed a known amount of eggs with a drop of sperm in water collected from our tanks- so we had 5 different pH treatments under which we carried this out. Then the hard work began; over the next 24 hours we had to check the stage of development. Initially this was just looking for a fertilisation membrane which shows that the egg has been fertilised. As time progressed we also had to count the cell stages. Just like the beginnings of a baby, the process begins with a single cell dividing into two, and then 4, and then 8 and so on. We have since repeated this experiment at a warmer temperature to see if this too had an impact on the speed of development or survival. Have a look below and see if you can see the ‘halo’ like fertilisation membrane around the yellow looking egg, and then at the 2 cell and 4 cell stages where the fertilised egg has begun to divide:

Top: Urchin eggs with fertilisation membranes & one 2 cell. Bottom: 4 and 8-cell stages. Photos: Hannah Wood

In other news spring has begun here in Ny Alesund- the first sign of which was the melting fjord. Since then we’ve noticed the roads around town turning slushy and eventually revealing the gravel underneath. The Eider ducks have arrived now that there is open water in the fjord and every now and again I hear the honk of a barnacle goose flying by. They will soon be arriving properly from their overwintering site in Scotland to lay eggs and rear their chicks. As the surrounding environment was changing so rapidly, Helen and I took the opportunity to go out and measure the conditions in the slushy seawater just accessible through the ice cracks, and also to see the conditions on the newly exposed rock where Helen’s barnacles are.

As the surrounding environment was changing so rapidly, Helen and I took the opportunity to go out and measure the conditions in the slushy seawater just accessible through the ice cracks, and also to see the conditions on the newly exposed rock where Helen’s barnacles are.

Helen Findlay measuring the temperature at the barnacle site. Photo: Hannah Wood

The Sunday just gone was Norwegian National day so the locals (and a few game scientists too) had a day of games and celebrations that began with a ‘wake parade’ with very loud drums banging and a badly played trumpet! There were several people wearing traditional Norwegian costumes and the day ended with a special barbecue at Magrallet Cafe. There were added celebrations when Norway won the Eurovision song contest the night before! It is quite an international community here so we all joined in and helped the Norwegians celebrate.

Ana-Krostoph (Left) and Bendik Helgunset (Right) in traditional Norwegian

costumes in National Day. Photos: Hannah Wood

So that’s us up to date. We put another urchin treatment in today so Thursday and Friday will be very busy sampling. The good news for us is that we have all the urchins we need now so have no more demands to make of the hard working divers. We are even hoping to spend an entire day out of the lab this weekend with a trip to a cabin. . .it’s a good incentive to work hard this week anyway 🙂

There are around 12 dogs that live here in NyAlesund. There is a long history of people bringing dogs to the poles with them, from the early polar explorers, to more recently Ranulf Fiennes who’s Jack Russell overwintered in Antarctica! Here in Ny Alesund though you are only allowed to keep Arctic breeds, like huskies. The main reason is that the dogs all live over at the dog yard, sleep in little kennels and have snow in their yards. So that is fine if you have nice thick fur to keep you warm, but the more delicate breeds would end up with very cold paws! They are not allowed to live indoors because everyone changes accommodation at times and huskies are a little stinky!

There are around 12 dogs that live here in NyAlesund. There is a long history of people bringing dogs to the poles with them, from the early polar explorers, to more recently Ranulf Fiennes who’s Jack Russell overwintered in Antarctica! Here in Ny Alesund though you are only allowed to keep Arctic breeds, like huskies. The main reason is that the dogs all live over at the dog yard, sleep in little kennels and have snow in their yards. So that is fine if you have nice thick fur to keep you warm, but the more delicate breeds would end up with very cold paws! They are not allowed to live indoors because everyone changes accommodation at times and huskies are a little stinky! I always associate the arctic with huskies, partly because I have dogs of my own so notice them, and partly because they form a large part of the character and feel of the place. Early in the evening you can hear them howling- more like a pack of wolves than dogs! I have since found out they howl like this when some of the dogs go out with their owners- the ones left behind get jealous and howl! The dogs here at Ny Alesund are all pets of the permanent staff, and in the long light evenings you often see people out with the dogs being pulled along on skis or maybe even a small sledge!

I always associate the arctic with huskies, partly because I have dogs of my own so notice them, and partly because they form a large part of the character and feel of the place. Early in the evening you can hear them howling- more like a pack of wolves than dogs! I have since found out they howl like this when some of the dogs go out with their owners- the ones left behind get jealous and howl! The dogs here at Ny Alesund are all pets of the permanent staff, and in the long light evenings you often see people out with the dogs being pulled along on skis or maybe even a small sledge!

saw her harness she gave a little bark of impatience as I stood there trying to work out which way round it went on! Helen and Bonnie joined me and we set off. We started with a trip round the village where I had a go being pulled along on a small sledge chair- this began successfully but kind of fell apart with a difference of opinion between Tinka and myself on the direction we should go- I thought the road track would be best but Tinker decided a sharp turn and into thicker snow would be better. I fell off. Okay, ski-chair abandoned we reached the corner of the village where we could go left to head out into the countryside towards the glacier, or right back to the dogyard and a bowl full of seal meat for dinner. After a brief exchange of words and battle of the wills Tinka decided maybe I was right and a walk would be nice so we headed off.

saw her harness she gave a little bark of impatience as I stood there trying to work out which way round it went on! Helen and Bonnie joined me and we set off. We started with a trip round the village where I had a go being pulled along on a small sledge chair- this began successfully but kind of fell apart with a difference of opinion between Tinka and myself on the direction we should go- I thought the road track would be best but Tinker decided a sharp turn and into thicker snow would be better. I fell off. Okay, ski-chair abandoned we reached the corner of the village where we could go left to head out into the countryside towards the glacier, or right back to the dogyard and a bowl full of seal meat for dinner. After a brief exchange of words and battle of the wills Tinka decided maybe I was right and a walk would be nice so we headed off. tracker (Helen) spotted some suspiciously large paw prints in the snow, but we concluded that it was from a dog a bit bigger than Tinka, phew! After about 4km we turned down towards the edge of the fjord. Typically they say to avoid the waters edge (polarbear risk) but as it is completely frozen it doesn’t really make any difference, but all the same we didn’t go right down to the edge! Once we moved away from the snowmobile tracks it was a lot harder to walk through the snow. Some parts were fine then you’d suddenly sink down to your knees in thick soft snow! I was able to use Tinka as my snow tester (unfortunatley I weigh a little more than her and she spreads her weight on 4 points not 2 so occasionally this plan failed) but Helen and Bonnie had no such help! Eventually we came across a reindeer track and followed this back to a scooter trail to make walking a little easier.

tracker (Helen) spotted some suspiciously large paw prints in the snow, but we concluded that it was from a dog a bit bigger than Tinka, phew! After about 4km we turned down towards the edge of the fjord. Typically they say to avoid the waters edge (polarbear risk) but as it is completely frozen it doesn’t really make any difference, but all the same we didn’t go right down to the edge! Once we moved away from the snowmobile tracks it was a lot harder to walk through the snow. Some parts were fine then you’d suddenly sink down to your knees in thick soft snow! I was able to use Tinka as my snow tester (unfortunatley I weigh a little more than her and she spreads her weight on 4 points not 2 so occasionally this plan failed) but Helen and Bonnie had no such help! Eventually we came across a reindeer track and followed this back to a scooter trail to make walking a little easier.

we looked at decided was wrong. . . and instead spent the morning moving around equipment and forming a plan of action that looked a bit like a urchin processing factory (do you get those. . ?). We had lots of urchins to get through and for each urchin the journey went something like this:

we looked at decided was wrong. . . and instead spent the morning moving around equipment and forming a plan of action that looked a bit like a urchin processing factory (do you get those. . ?). We had lots of urchins to get through and for each urchin the journey went something like this: Urchin plus pot was brought to the sampling by

Urchin plus pot was brought to the sampling by  The sea urchin experiment (Study 6) is now up and running so I thought now would be a good time to fill you in on what we have done.

The sea urchin experiment (Study 6) is now up and running so I thought now would be a good time to fill you in on what we have done.

Then on Saturday the mission to begin the experiment began. It took three of us working together; I used a net to fish the urchins out of the holding tanks. I then weighed them and passed them to Karen, who measured their diameter. Steve then took the urchins through to the main experiment room and randomly put them into the exposure pots. We were quite pleased with our efforts and the whole thing took about three hours. We went off to dinner quite satisfied with our work.

Then on Saturday the mission to begin the experiment began. It took three of us working together; I used a net to fish the urchins out of the holding tanks. I then weighed them and passed them to Karen, who measured their diameter. Steve then took the urchins through to the main experiment room and randomly put them into the exposure pots. We were quite pleased with our efforts and the whole thing took about three hours. We went off to dinner quite satisfied with our work.

As we went around returning them to their pots, and finding it all quite funny, it was decided to use elastic bands to keep netting in place on top of the pots. Steve was flying out that day so the task fell to myself, Helen and Karen. It started well but putting your hands in water that is zero decrees Celsius (this is the temperature freshwater freezes but because of the salt in seawater it does not freeze until it is around minis 2 degrees Celsius) soon meant our hands became clumsy and the elastic bands seemed to have a life of their own!

As we went around returning them to their pots, and finding it all quite funny, it was decided to use elastic bands to keep netting in place on top of the pots. Steve was flying out that day so the task fell to myself, Helen and Karen. It started well but putting your hands in water that is zero decrees Celsius (this is the temperature freshwater freezes but because of the salt in seawater it does not freeze until it is around minis 2 degrees Celsius) soon meant our hands became clumsy and the elastic bands seemed to have a life of their own!